90% of Times Validation Means Invalidation

Validation plays a pivotal part in famous startup success stories. If we consider the data, we should rather focus on effective invalidation.

In the early stage of product development, we talk a lot about validation. We first look for problem-solution fit. It tells us whether there are at least hypothetical customers for whatever we want to offer.

Then, we turn to product-market fit. That, in turn, tells whether we can earn money building the product we ideated.

Whenever we approach either of these challenges, we only have a hypothesis. We don't know whether it would work, so we design experiments to prove that our assumptions are right.

Zappos' Validation Story

Imagine it's the dusk of the old millennium. The internet bubble is the thing, and no one yet expects it to pop soon. You watch as people buy shoes (yup, in actual stores) and you think.

They have to spend time going from one shoe store to another, trying to find what they are looking for and then hoping their size will be available. You wonder. What if they could browse shoes in the comfort of their sofas? They'd spare themselves the effort, and the shop would get the correct size sooner or later.

Well, obviously, selling shoes over the internet is far from a sure shot. Would people even buy shoes they can't try on? Would they be willing to wait for the delivery? What if they don't like their purchase?

In other words, while you see a problem, you aren't sure if you have a solution people want. So you validate.

In 1999, Zappos' founder—Nick Swinmurn—built something pretending to be what we'd now call an e-commerce site. While it listed products, there wasn't any stock whatsoever. Whenever anyone "bought" a pair of shoes at ShoeSite.com, Nick would run to a local shoe store to make the actual purchase and ship it over to a client.

With enough customers, he validated that he, indeed, had a solution to a problem.

The next question was whether it could be a profitable business. Clearly, Nick's capabilities to fetch orders were limited. The website was renamed Zappos and started working as a real e-commerce site.

With enough traction over time, he validated product-market fit. The business had potential.

Airbnb's Validation Story

Imagine it’s 2007. Almost a decade has passed. The financial bubble is nearly ready to pop, but very few people have enough insight to worry about that. The IT industry has recovered from the dot-com boom and its subsequent crash.

You host occasional guests in your living room on an air mattress to earn a few extra bucks. A few of your guests mention that they appreciate the affordability of the stay at your place.

You wonder. Is it a problem more people might have? Probably. Would your idea—renting an air mattress in a spare room—be a good solution for a broader audience?

In 2007, Airbnb's founders decided to validate precisely that. They built Airbedandbreakfast.com, whose launch they coordinated with a major conference, hoping that the scarcity of lodging would help to boost interest.

Indeed, they secured a decent number of bookings. They validated that their idea solves someone's problem.

The next step? Figuring out whether they can turn it into a business. The best way to do that? Let people vote with their credit cards. Airbnb added a payment system, and people, both travelers and hosts, kept coming.

They validated product-market fit. And yes, these days, it's easier to book a castle than an air mattress in someone's living room.

That's, by the way, also an outcome of continuous validation. The features that work stay. The ones that don't, go.

Survivorship Bias

You go through these stories, and it's validation all along. Look at any startup that grew into prominence in the last two decades, and you'll spot the same pattern.

There's definitely business acumen, being in the right place at the right time, a healthy dose of luck, vision, hard work, and more involved. Yet, when you look at product development, it's all about validation. Successful validation, let me add.

If there are bits about bad ideas, positive turnarounds quickly follow.

And it's a wrong picture altogether.

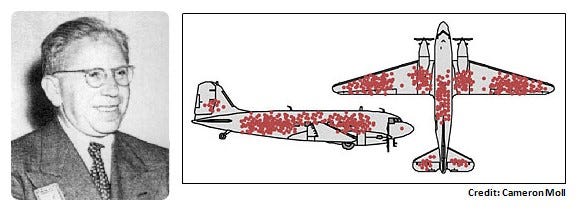

It's the equivalent of Abraham Wald's analysis of bombers' damage after WWII sorties. The patterns clearly showed that some parts of the plane were more likely to be peppered with bullet holes, and the engineers were quick to reinforce these parts.

What Abraham Wald saw was a completely different picture. The damage to these parts wasn't critical as the airplanes limped back to the bases. The missing data was from aircrafts that didn't make it.

In fact, the least—not the most—damaged areas required reinforcements. The engineers were fooled by the phenomenon we today call survivorship bias. By not considering the data they didn't have easy access to, they came to conclusions that eventually cost many crews their lives.

It was Wald's insight that turned the commonly accepted practices entirely.

Odds of Failure

When considering the startup ecosystem, we routinely agree that 90% of startups fail. By the way, I equally routinely suggest asking about details whenever someone quotes this number.

The context matters. What is a startup? What is a failure?

Do we consider a sustainable, bootstrapped business that never scaled a success? It never grew, so by VC standards, it's a flop.

Do we consider, say, Foursquare a success? It had hype and valuation back in the day. It still exists. But the investors are never getting their money back. Not all of it, at least.

Anyway, it's another discussion. We probably do agree that a huge portion of products ultimately fail. For the sake of this argument, I can stick to 90%.

All these validation stories I mentioned earlier are basically a clinical case of survivorship bias. They are but bullet holes in the wingtips. We don't see the holes in the engines or fuel tanks. We don't see cases of invalidation.

What's more, a disproportionately small number of survivors in the data sample makes the mistake even more harmful. We should not try to learn how to validate. After all, we'll end up with this outcome only 1 out of 10 times.

We should learn how to invalidate.

Well-Designed Experiment

I really like Don Reinertsen’s frame of what constitutes a well-designed experiment. He suggests that an experiment should have roughly equal chances of succeeding and failing. In other words, the outcome is uncertain.

The reason is that, with such a design, we get most new information. If we planned a trial we expected to fail, and it did, we learned little. Ditto when we expected success and landed it.

The game changes, however, when we have a favorable payoff curve. In layperson's terms, the cost of an experiment is low, but the potential payoff from succeeding is disproportionally high.

In such a case, the "experiment economy" would suggest that we run experiments that are likely to fail. Ideally, we try many of them to hedge our portfolio against a few failures.

Imagine paying a buck to roll a d20 (20-sided) die, and each time you roll a twenty, you get $50. A couple of such rolls will likely cost you $2, but roll the die a hundred times, and you can take your loved one for a fancy dinner.

With early-stage products, we play a similar game. The vast majority of our ideas are not going to fly. That applies to both big (products) and small (features) experiments.

The similarity extends further. The payoff of a successful product can be really high. I'm as far as it gets from picking unicorns as our role models, yet even a mildly successful, bootstrapped startup will fit this picture neatly. In this space, the payoff curve is asymmetrical.

In other words, our experiments will necessarily be skewed toward failure.

Validation versus Invalidation

All these building blocks create a clear picture. In an early-stage startup, or any early product development effort, really, we will be invalidating much more frequently than validating.

Moreover, the faster (and thus, cheaper) we can invalidate, the better. It only means that we'll survive to roll the die a few more times and maybe land our natural 20 on a lucky roll. We extend our runway and improve the odds of succeeding. What's not to love?

The mindset here is crucial, though. It's not a game of trying hard to make it work. It's a game of quick tests and quick discards.

It's nothing like ShoeSite.com evolving into Zappos.com and soon after claiming the world's biggest shoe store title.

It's not like Airbedandbreakfast.com evolving into Airbnb.com and growing steadily ever after until becoming the second most popular hospitality site on the internet.

Statistically speaking, these are outliers and relatively rare ones. As inspirational as they are, very few products will follow similar paths.

For the rest of us? Learn invalidation. Rapidly. Aggressively. Ruthlessly.

Because validation 9 times out of 10 means invalidation.

There’s one “benefit” from running experiments quickly to find out what DOES NOT work:

we remove things from our list of work to do.

In other words, the more (quick) experiments we run, the faster we will narrow down the list of ideas - which makes it both faster and cheaper to actually produce the right product.

The BIG problem is when we don’t INvalidate, but rather focus on VALIDATING, which leads to more work: slower and more expensive…

While rapid invalidation is statistically smart, founders need rose-colored glasses to maintain momentum. The constant "no's" from validation experiments can shatter those glasses and deplete the vital energy needed for perseverance.

Perhaps the best approach is reframing validation as a creative discovery tool - not just testing if you're right, but uncovering what's truly valid about your perception of the problem you're passionate about solving.