Dear Startup, Build Less

The single most critical advice for founders? Build less. The single most useful leverage to achieve that? Overconstrain your budget.

If there's one universal advice I'd give just about any early-stage startup founder, it's “build less.”

Over 20 years of building products at Lunar Logic, I recall no single situation where suggesting an additional feature on top of what our clients already wanted would have been the right decision.

Not a single one.

I don't say it's impossible. It's just that it's been so rare that I can't recall such a case.

Now ask me about cases where our clients wanted to build too much, and I’ll be like "Do you have, like, a spare week or something? Because I can bore you to death with such stories."

The Evidence Doesn’t Lie

Sure, it's just anecdotal evidence. Over the years, we contributed to (or built entirely) perhaps 200 products. And while we've worked with a diverse group of clients, our attitude remained largely the same. We never pushed for building more, even if it would be, well, more paid work for us.

Then, there's confirmation bias, too.

And yet, the sheer disproportion in the availability of data for either scenario is gargantuan.

I often refer to all the products pitched to us, whether we have or have not ended up working on them. I lost count, but by now, the total number of them would be in the 4-digit territory. The founders often describe their ideas as MVPs. Across all those pitches, I'm yet to hear one that I would consider minimal.

So it's either of the two.

Either (at Lunar Logic) we have an unjustified tendency to suggest building less, while, in fact, we are utterly wrong and building more is a winning strategy.

Or we actually learned a thing or two after helping so many startups at their earliest stage, and it's a common practice of building a lot that's a bad move.

It’s Both Theory and Practice

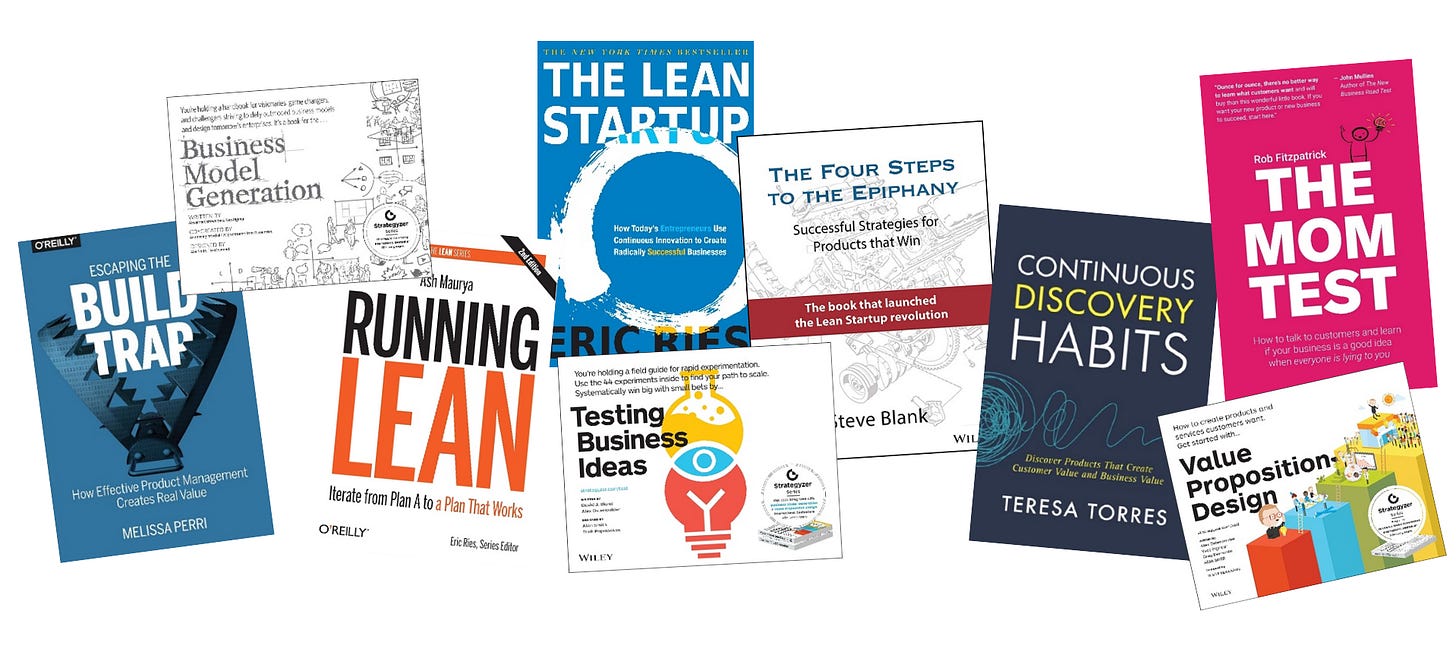

If I were to summarize a swath of books on product development in one sentence, it would be the following:

Challenge every assumption, build as little as you can get away with, release early, validate relentlessly, learn from feedback.

It's the theme that you'd pick from just about any book from the picture above. From Eric Ries to Melissa Perri. From Rob Fitzpatrick to David Bland.

By the way, I apologize to all the authors for vastly oversimplifying everything they shared in their work. Yet the theme is there. In every single one of them.

The other argument is the actual reality of our work. We do see product development efforts going live. And it's... underwhelming. Not a surprise, right? The startup success rate is appalling.

However, a good question is: why? Why do all these products fail?

The answers are many, but none of them are too few features.

Why Do Products Fail?

The common reason for failed products is that they fail to build enough of a business case to sustain themselves.

There aren't enough customers, or they churn. Or they don't pay enough. The competitors may play fiercer than founders thought. Or the problem to solve was artificial from the very beginning. I've seen products killed by legal issues, privacy concerns, technology advancements, and personal conflicts, too.

According to various statistics on startup failure reasons, the top one is typically "ran out of funding." Which is funny. It may be an immediate reason for a company to go out of business, but it is not a root cause.

The runner-up reason for startup failure is a variation on "lack of Product-Market Fit."

One could argue we might rephrase it as not enough features. But it's a flawed perspective. A lack of Product-Market Fit (or earlier Problem-Solution Fit) means that we're building the wrong thing altogether. If we added some more to it, we might have made it even wronger. But that’s just about it.

If there's any rephrasing of this class of failure reason, it's that there was no (or not enough) validation. As a result, we kept building the wrong thing till the money ran out, and then, well, game over, no final uplifting cutscene for you.

Why Is It So Hard to Refocus on Validation?

I started with my single best go-to advice for founders: Build less.

A good response would be: But how?

Validate. Validate relentlessly. Assume everything might be wrong unless you have the data to prove otherwise. Such an attitude means that we uncover, identify, select, and verify one assumption after another.

Ideally, we do that with the least possible effort. After all, 90% of the time, validation means invalidation.

Easier said than done.

We have a natural tendency to:

Be overly positive (and thus, believe something will work without validating).

Lean toward efficiency (and thus, pack a few separate hypotheses into one work effort)

Ignore confirmation bias (and thus, ignore data that goes against our intuition or belief)

Even when we say we aim for early validation, we still build way too much. Thus, my experience with MVPs ("always a product, sometimes viable, never minimum").

It's just so hard to rewire our beaten thinking avenues to something very different, even if we intellectually know we would have been better that way.

How To Put Validation at the Center?

I use one trick to help founders break out of their default mindset and get them laser-focused on validation. The algorithm is pretty straightforward:

I ask about the budget they have for an MVP (I don't even need to know the number; it's key that they know what it is).

I ask them to divide it by 10.

Then we explore together what's possible within the new constraint.

The whole trick is that with just 10% of the original budget, you can't play the reduction game anymore. Starting with an "MVP" and removing some least valuable features simply won't do.

You have to redefine the whole process.

As a reference, typical numbers we play with here are $50k-$100k, which founders have in mind to get the initial product to market. That's reasonable. Probably more than one would need to get a true MVP, but when we talk about "MVP," that's constraining enough.

So get that down to five of seven grand and ask yourself, what can you get for that?

Suddenly, you're no longer in the area of "building a product." You have a very modest budget for some experimenting.

The Mindshift

The whole trick is to get founders far enough from their initial plan of building a product, so that we can take two steps back and restart with ideation.

You won't build a product for $5,000. Sure, you can vibe code a prototype, but it won't be a product, even an early version of one. In a way, with this little mind trick, we force ourselves to abandon the old mindset.

Instead of asking how much my MVP would cost, we ask what is the most valuable thing I can get for a few thousand dollars? The answer to the latter is never building a first version of a product.

It may be a vibe-coded prototype. Or better, a pretotype. We might double-down on user interviews. Perhaps extended research can provide us with the most valuable insights. In some cases—especially with AI-heavy ideas—technical proof of concept may be the way to go.

Each of these scenarios is a better validation vehicle than jumping straight to an MVP development. And despite our sentiment toward building more, we ruled it out as an unfeasible scenario when we set the budgetary constraint.

Even better, if anything we commit to yields little outcome, we lose very little. Because, you guessed it, our tight financial constraint.

Oh, and in such a case, we still have 90% of the budget for exploring alternative paths in a similar manner.

One little trick, and it does so much on all fronts. A sad thing, it’s so counterintuitive.

Build Less

There's hardly better advice I could give early-stage founders than "build less."

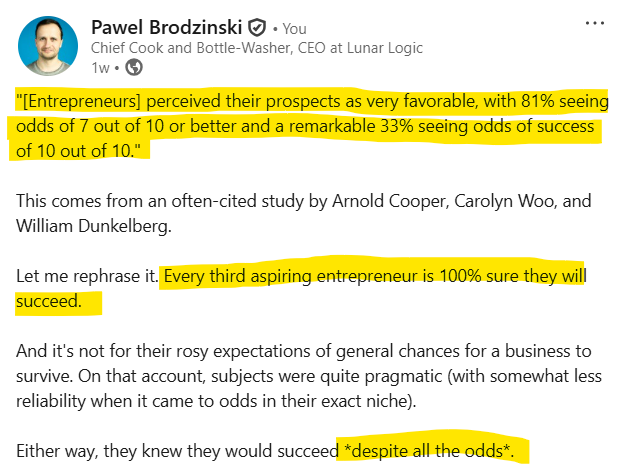

Having said that, I'm a pragmatic person. I acknowledge that the advice itself does little. We are primed to default to building a lot because we believe we will succeed.

We believe against what we know. We believe against all odds.

Asking to stop believing that is a tall request. Instead, we can redesign the game so the default path is no longer available. And it comes with minimal risk, which is a neat bonus.

What's not to love?

The "build as little as you can get away with" advice makes sense, but how does one actually know when one has hit that minimum threshold?

What if one builds minimal, gets negative feedback, but adding just one feature (or improving the UI) would flip user perception from negative to positive? How does one distinguish between "validate more" and "we actually need this one thing"?

It seems like there's a real risk of under-building just as much as over-building, especially when user behavior doesn't always match what they tell you in interviews.