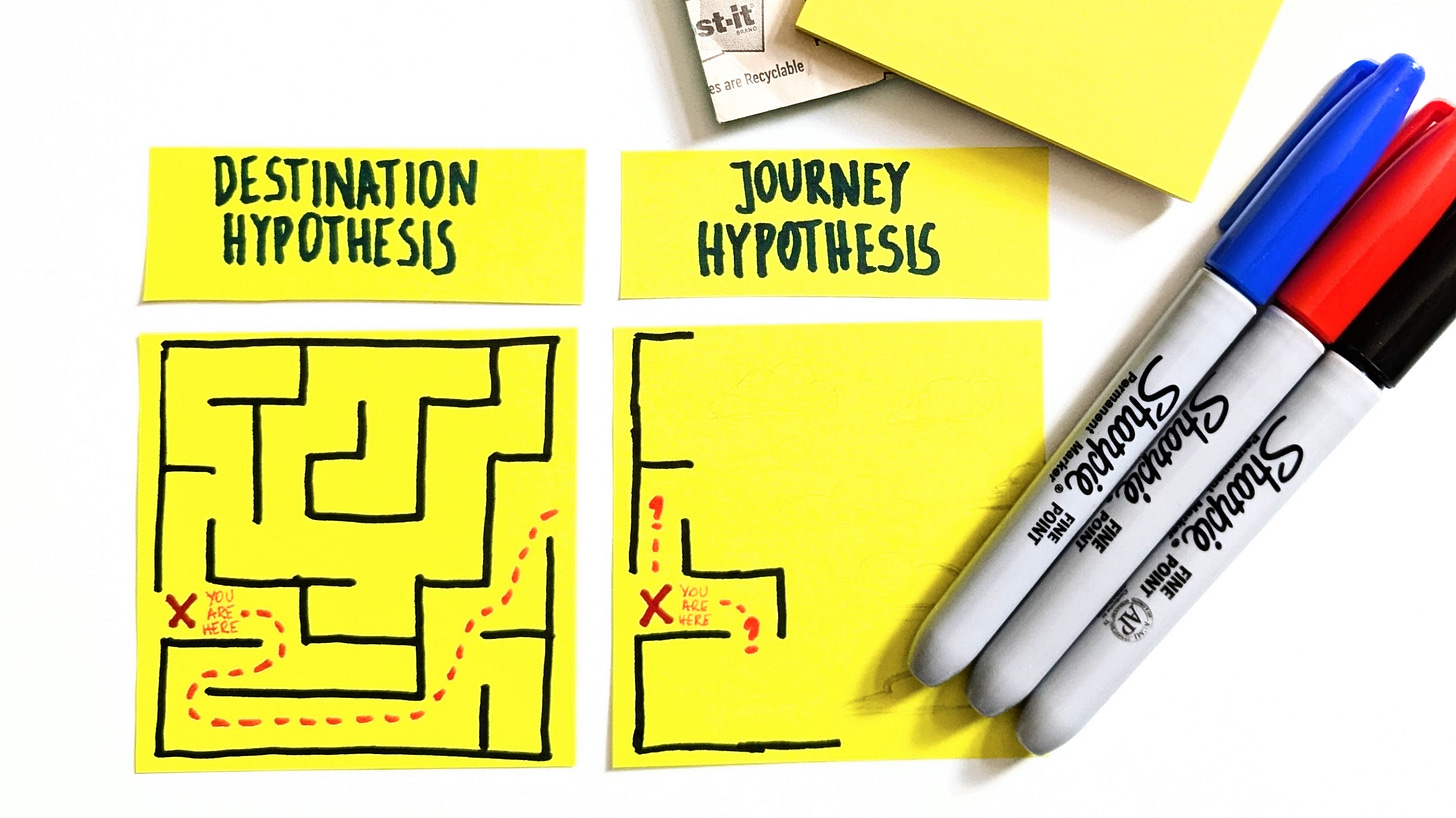

Journey Hypothesis or Destination Hypothesis?

It's about a journey, not a destination. Building a startup is exploration and not following a pre-planned route. Even if we make such stories in retrospect.

When we build stories of successful startups, it's easy to paint a consistent path that brought them to where they are.

Amazon figured that selling books online must be viable as the internet was becoming popular. Once they dominated the original niche, it was only reasonable to expand to others and become an everything store.

Zappos started with a less obvious product—selling shoes online—but they validated the idea and then scaled the business fast. They couldn't move into other niches as Amazon was already there, so they sold the company, well, to Amazon.

Airbnb started by renting an air mattress in the founders' flat, then moved to alternative lodging around major events, and eventually expanded to short-term rent of anything, everywhere.

Heck, take Lovable, THE darling of the startup ecosystem. They figured that with current AI capabilities, you could generate a functional app with a prompt. Then they doubled down on the idea to become the fastest-growing unicorn ever.

In retrospect, all these stories are like highways leading to a known destination. That's, in fact, the whole problem: "in retrospect."

Rocky Paths

Sure, not all roads to success look that straightforward even in retrospect.

The Slack story starts as a multiplayer game that was a flop. The internal tool that the team had developed for communication seemed salvageable, though. And salvageable it was, indeed.

Way less prominent, although a surprisingly similar story is Flickr's. A photo-sharing feature designed to improve the retention of a multiplayer game quickly proved to be more popular than the game itself. Thus, the stand-alone product was born.

Fun fact: A few years later, Flickr's founder invested in Slack.

While Rovio may not sound like a household name, it's the company behind one of the first gargantuan successes of mobile gaming—Angry Birds. Less well-known is the fact that Angry Birds was their 52nd attempt to succeed (and probably the last, given that at the time of building the game, they were on the brink of bankruptcy).

Also, the last decade wasn't rosy for Rovio. Yet, the biggest highlight of the time is when they were true to their original mission and released a remake of the original game.

Again, all these stories make sense in retrospect. Even if the original idea wasn't a home run (no idea is, really), it's all about finding that one bit that works, doubling down on it, and they lived happily ever after.

Even the problems seem to correlate with departing from the validated vision.

The Destination Hypothesis

When reading those stories, we build a pattern:

Figure out the destination (product, offering, etc.)

Validate it works

Focus on getting to your destination as efficiently as possible

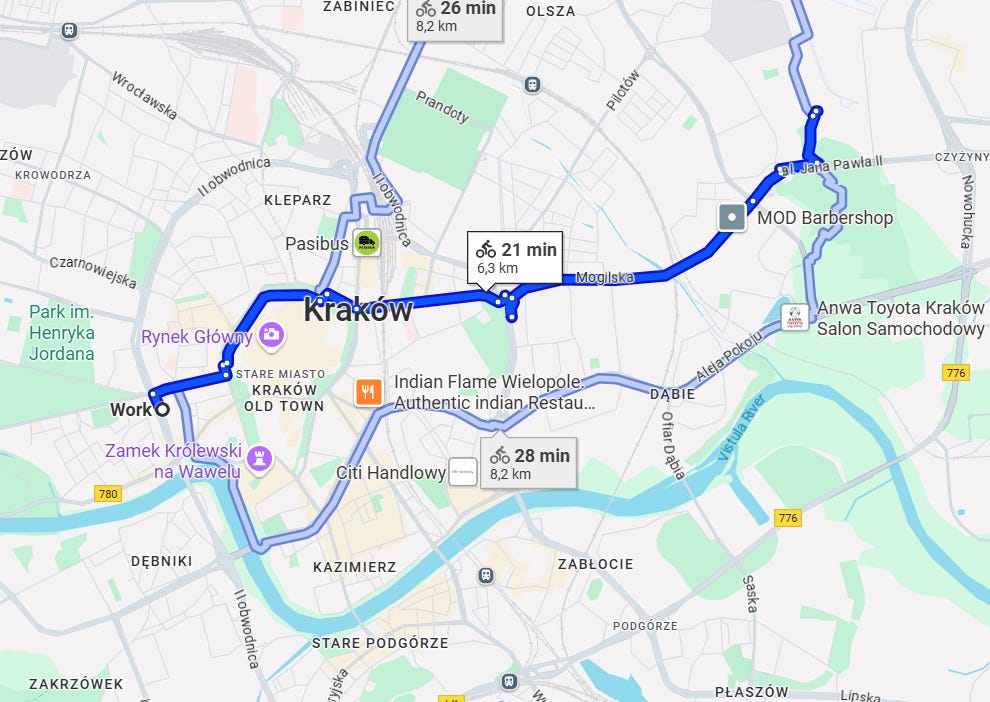

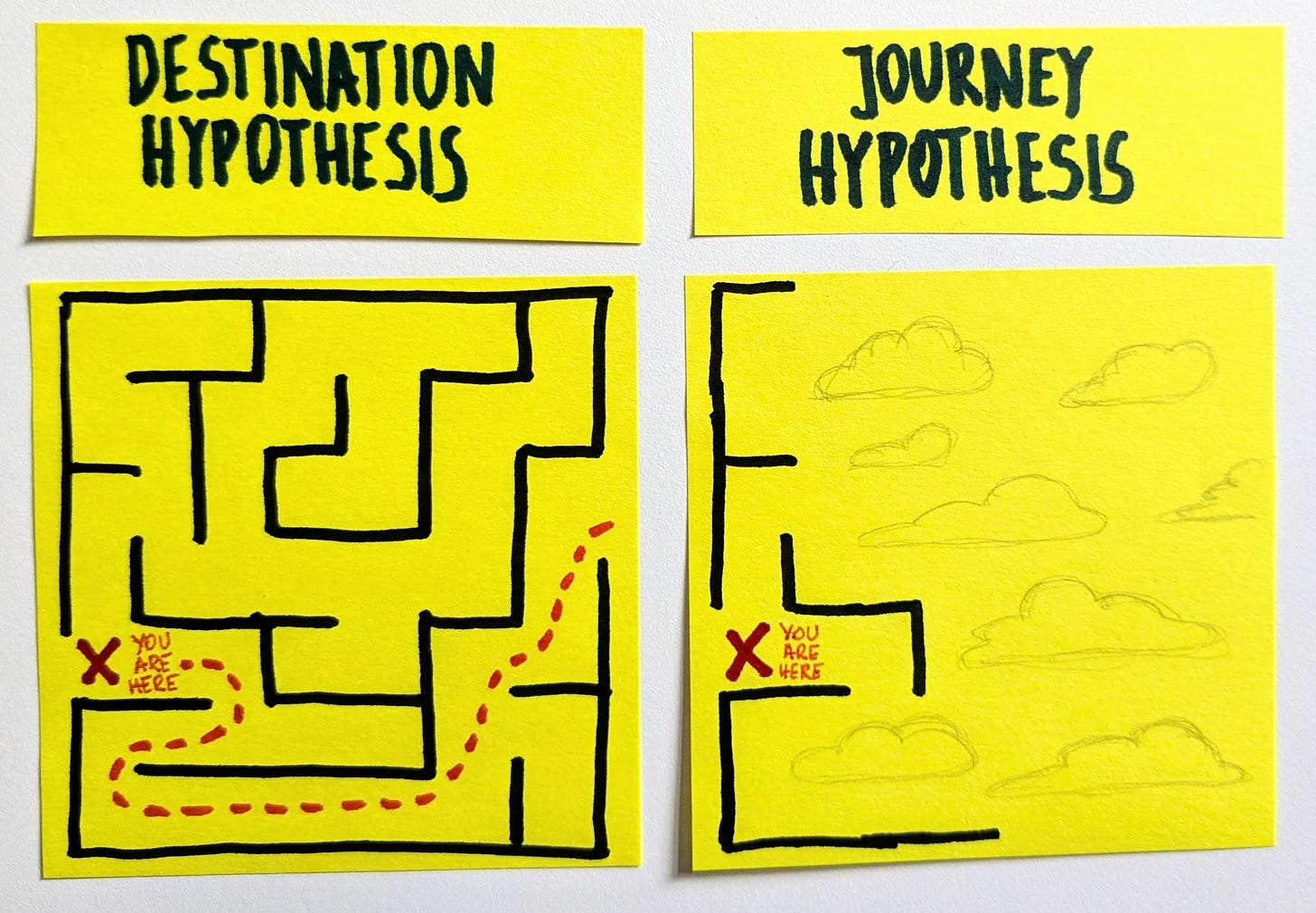

With such a pattern in mind, it's easy to go with a metaphor of planning a route to a destination. It's like on a map. You are here. You want to be there. Dear Google Maps, can you please find me the best route to get there?

If we know the destination and a good route is knowable, we can focus on getting there efficiently. We can play with optional detours or alternative means of transport, etc.

In the product development context, it translates to having a relatively accurate vision of a target product (the destination). Once we have that settled, we can switch to optimizing the efficiency of building it (the route).

I will call this way of framing product development the destination hypothesis.

The Journey Hypothesis

An alternative approach altogether is to assume we don't know where we're heading. Think of it like starting a trip into the wilderness. While you know where you start, you don't know where a good place to camp would be.

You may define a desirable outcome in vague terms: a nice clearing, ideally with a fresh water source, and no other hikers staying too close. Where is it, though?

You might have some ideas, and the map may suggest a few options to you, too. Yet, you won't learn about how lovely the place is or whether others have already taken it unless you check it.

In other words, you set out to explore and validate some of the spots you can think of. Possibly, you are on the lookout for lucky finds, too.

In the product development context, it translates to acknowledging that you don't know the product you're going to build. You have hypotheses that you aim to validate one by one. Ideally, in order from the most to the least risky one.

I will call this way of framing product development the journey hypothesis.

It’s About a Journey, not a Destination

Which metaphor works better? When traveling, it depends on the context. Yet, statistically speaking, we rely on the destination hypothesis much more often than on the journey hypothesis.

What's more, we're psychologically primed to choose the destination hypothesis. As Daniel Kahneman in his fabulous book Thinking: Fast and Slow points out, we hate uncertainty—we'd prefer to be wrong rather than uncertain.

The problem is that in early-stage product development, the usefulness of the destination hypothesis is limited.

Sure, there are whole classes of products that lend their hand to that approach. One obvious example is whenever we're automating an existing (and profitable) business activity. But then? Not much more generic cases.

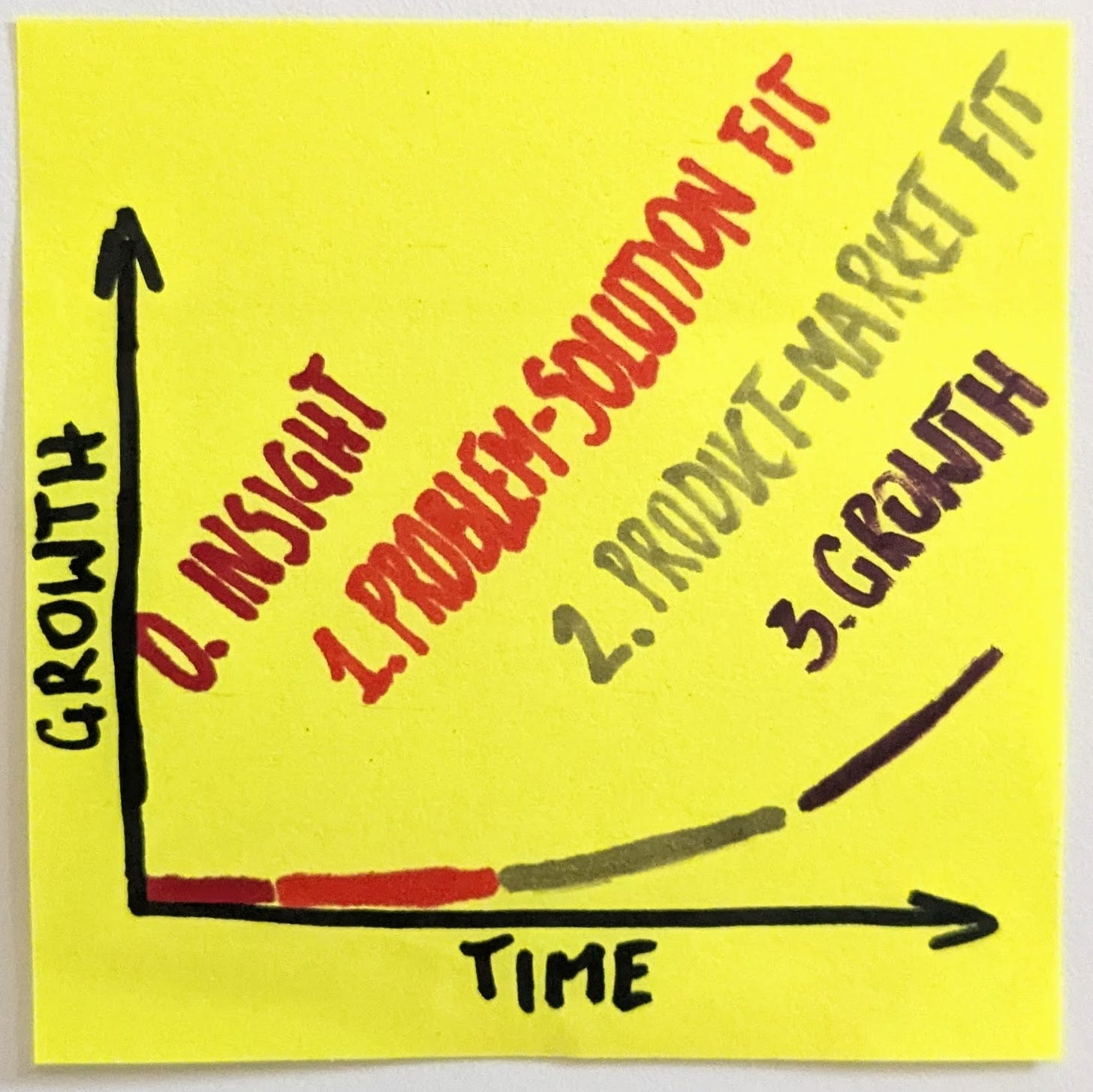

Statistically speaking, though, the vast majority of product development effort is focused on creating an entirely new value stream. At the most generic level, we go through the cycle of:

Identifying a problem we want to solve

Finding an appealing solution to that problem

Offering a minimum product that does the trick

Validating whether we can sustain the business with it

It is exploration at its very core.

It doesn't fit the destination hypothesis. It's the journey hypothesis all the way. Well, at least until we find and maintain Product-Market Fit.

What Is the Ultimate Goal?

Aside from how we're planning a trip, there's one more key distinction between the hypotheses.

For the destination hypothesis, the goal is to get there efficiently. After all, we know where we're heading. We know where “there” is.

For the journey hypothesis, the goal is to find the right place. After all, we don't yet know where we will spend the night. It’s unknown. Heck, it’s unknowable up front.

In the product development context, the destination hypothesis tells us to double down on building. A big team working concurrently on the whole initial feature set would be preferable. After all, it will deliver the entire scope faster. Alternatively, we can dream of becoming a solopreneur with a billion-dollar business.

Conversely, if we follow the journey hypothesis, we don't want such a pace of development. Not at the cost of a big team. We want to explore our business assumptions, validate (or more likely, invalidate) them, and only then decide on the next steps.

That's, in fact, a crucial difference. Validation takes time. Once you have your prototype, you still need to get it in front of customers and learn what works and what does not. Then, you adjust your course.

It's like the difference between solving a maze puzzle with and without the fog of war.

The Route Emerges Only In Retrospect

I know, most of the time, founders believe their product will fly. They are in love with their ideas. That's why they default to the destination hypothesis.

That makes sense. If I'm 100% sure my thing will succeed, all the exploration is a waste of time and resources. All the exploration is just trying out paths that we won't travel.

And yes, many early-stage entrepreneurs are that sure of themselves.

"[Entrepreneurs] perceived their prospects as very favorable, with 81% seeing odds of 7 out of 10 or better and a remarkable 33% seeing odds of success of 10 out of 10. "

Arnold C. Cooper, Carolyn Y. Woo, William C. Dunkelberg

In reality, there are very few cases where the destination hypothesis works for early-stage product development. It would mostly be limited to automating existing processes, some scaling problems, and some replacement products.

Everyone else should operate under the journey hypothesis.

Yes, once you succeed, your journey will look like you knew the path all along, but that simply isn't true. Amazon, Airbnb, heck, even Slack or Flickr's paths all look like there was a route.

But there wasn't one. It just looked like there was, in retrospect.

It was a journey, not a destination.

There’s a follow-up essay to this one, which explores how the destination hypothesis dooms many early-stage startups.

I always say that in the beginning you don’t even know the right questions to ask. You even have to discover them.

Building a thing - a product, a company, whatever - is like going on a treasure hunt but without the map. You are also responsible for discovering and drawing the map.

It won’t be easy, adventure, sharks and lions await. Enjoy the ride or just skip it. It won’t happen without a bloody nose … or more. Which is ok.