Alternative Statup Playbook: Aiming for Early Profitability

Profitability is suspiciously absent from many narratives about startup health metrics. Startups that focus on early profits (not just revenues) seem to play a different game.

OpenAI doesn’t expect to be profitable until at least 2029. That’s according to their predictions. It’s not hard to find more conservative estimates, though.

Either way, it will be around 15 years to see their first dollar of profit. Meanwhile, they’re burning funds that, only a few years ago, we’d deem unthinkable.

Lovable claims to be the fastest-growing startup ever. They blitzed their way to $100M Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR) and became the darling of the startup industry along the way.

Yet, if you look for any traces of future profitability, the information is surprisingly scarce. Considering their ARR in the context also tells a somewhat less rosy story.

Profitability seems to be “a thing for the future”. And it’s fascinating how we’ve started accepting that perception as the norm.

Inattractive Profitability

Sure, we often recount the stories of the biggest successes of the 2000s, which were all about scaling first and figuring out the business model later. Except we conveniently forget that Google was profitable in its third year. Facebook was in its sixth.

Compare that to OpenAI’s fifteen (still speculative).

Imagine you start a small business. A grocery shop. Or a software shop, to stick with our context. How much time do you have till break-even? Only as much as you can shoulder the ongoing losses. A few months? Half a year, maybe?

Definitely not fifteen years.

The availability of funding distorted the playing field. We somehow got to believe that building something for years, while continuously burning millions, is a feasible business strategy.

And boy, do we have plenty of evidence. The startup playbooks will be all about revenue (ARR) and revenue per employee as key metrics. Profits? Yeah, but if a company is already profitable, who would need investors by that point?

Bootstrapping as the Profit-Focused Strategy

If we flip the script and avoid external funding, we suddenly play a vastly different game. We are that small business with a short runway, except in the digital product plane.

We can afford to lose some money for some time or some more money for a much shorter time, but that’s it. We then need to sustain the company through ongoing revenues.

We need profitability.

In fact, that’s the centerpiece of the entire business. A bootstrapping startup subordinates all the operations to that. If we can’t afford to hire another person, we don’t. If it means we abandon the rapid growth strategy we ideated, so be it.

What’s more, bootstrapping encourages a startup to care about long-term revenues as well. It makes no sense to harm future revenues just to make some quick money. That is, unless the latter is absolutely necessary for survival.

Since we don’t try to win a pitching contest, there’s zero reason to fudge the numbers.

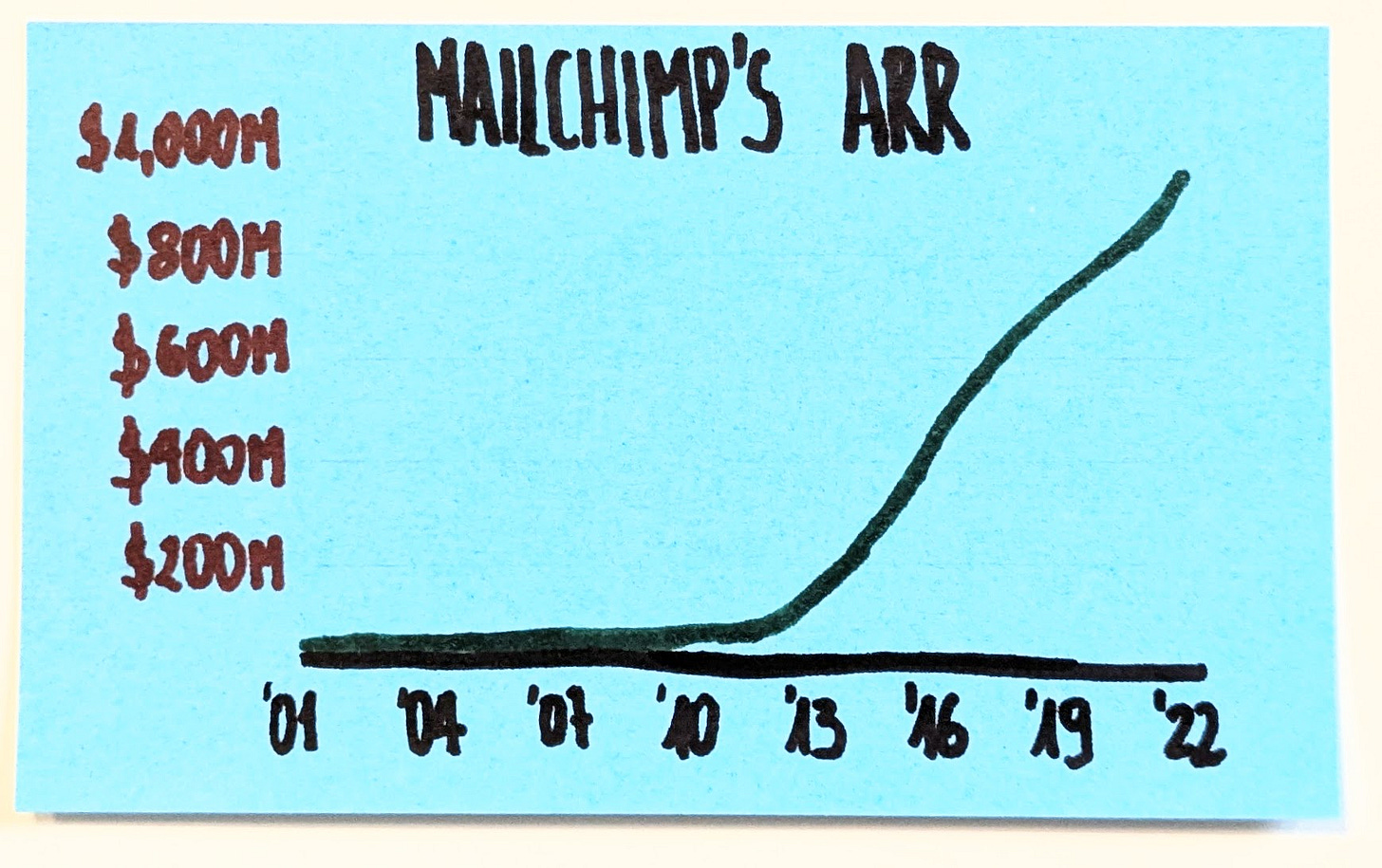

Mailchimp Story

Here’s a common argument: Bootstrapping means that we subordinate growth to profitability. And that, in turn, will allow our competitors to outpace us. Then, it’s a game over. Correct?

Not necessarily so. Mailchimp is a neat example.

The company was started in 2001. Yup, just after the internet bubble popped. There can hardly be a worse time to start an internet product.

For the first six years, it was a side hustle for the founders. It’s against what you would hear from just about any investor. They insist on complete dedication and laser focus on growth.

The service was paid from day one. In fact, the freemium model became an option only in 2009. The goal was always Mailchimp’s sustainability as a business. As soon as possible.

Over the years, they grew only at a pace justified by revenues. Team growth was the outcome of business growth, not the other way around. Again, going completely against the most common startup playbook.

The founders refused all the offers of external investment till they eventually—after 20 years—sold the whole company for a whopping $12B (still owning 50% of shares each). Once more, swimming against the startup world tide.

Mailchimp basically went against every playbook that existed at the time. While there’s no data to say precisely when they became profitable, we can safely assume they were so almost from the outset.

Slow initial growth didn’t kill them. A lack of an aggressive growth strategy didn’t make them fail. Many competitors along the way didn’t steal their market.

When Intuit bought Mailchimp, it was basically a sure shot.

Heck, could even explore what-ifs. What if Mailchimp hadn’t offered the free plan in 2009? After all, the freemium model was behind their rapid growth.

A funny thing, they’d still be a profitable company doing perfectly fine. They wouldn’t sell a dozen years later for 13-digits, but it would still be a success story. Not as a prominent one, but a success story nonetheless.

Which aggressively funded startup aspiring for hockey-stick growth can say as much?

Why Isn’t Bootstrapping More Popular?

We always have the holy grails of startup metrics. These days, recurring revenues (ARR) and revenues per employee (capital effectiveness) would make it to the top of the list.

It’s almost fascinating why profitability isn’t there.

I say “almost” because, as much as it seems like it should be an obvious idea, there’s a good explanation. If there were more Mailchimps among startups, we wouldn’t need nearly as much external funding.

In other words, we wouldn’t need so many VCs. And since the investors are the most influential caste in the entire ecosystem, they play their tune: “You need to get funding, otherwise you can’t grow fast enough (and make enough money for us).”

If early profitability were the ultimate goal for every startup, the appetite for externally sourced money would be significantly lower. VC money would be more like the last resort rather than a default avenue, which it is now.

We would also see more startups that stop midway. There are companies that are past the break-even, but don’t show promise of exponential growth. For people running such a company, sticking to their guns while recalibrating their aspirations may be an attractive proposition.

For VCs, it is not. It simply doesn’t promise returns that are high enough to justify all the other losses. Thus, an investor would always push for growth. Midway is not good enough.

Profitability From Day One

There are two trends that I see with the emergence of AI.

One is that, increasingly, product companies focus on paid plans almost from the outset. The reason is that running the AI infrastructure is costly. A free user is a substantial, not marginal, cost. Thus, freemium is no longer nearly as attractive an option as it once was.

Another is that AI tools have reduced the cost of experimenting with new ideas. The spaghetti strategy (throwing spaghetti at a wall and looking at what sticks) is much more viable than it was. While it’s not a sustainable product development tactic, it may be a good starting point.

Combine the two, and you have a Petri dish for profitability from day one. I don’t say it’s a slam dunk, of course. Product development has never been so. No change on this front.

Sure, the barriers are as much removed for us as for any willing competitor who wants to enter the same niche. Having said that, success in product development was never about the pace of building.

While the new landscape has its own challenges, bootstrapping (and early profitability) in digital product development is more viable than ever. Even if it’s something that you won’t hear from VCs.

The "Profitability From Day One" idea seems tasty. What if the product is at a very early stage...

Let's assume we've a vibe-coded pretotype.

Problem: At events, one meets 20+ people per day, and to make each new contact worth anything, a good (accurate and personal) follow-up is necessary. The cognitive load during events is crazy, and it's impossible to remember enough relevant info. Business cards and LinkedIn profiles won't give you the context of your chat. Quick mobile or random pieces of paper notes are easily lost, or cost too much energy to keep them organized.

App workflow:

1. Meet someone (potential client, investor) at the event

2. Connect your LinkedIn profiles by scanning their QR in our app

3. Add context notes about conversation

4. After event, export contact list with all the context

5. Send personalized follow-ups, without wasting time recalling long-gone memories or decoding gibberish notes.

Would you:

a) start showing the app for a 5$ (small) subscription, to be "profitable day one"

b) freemium, to validate the idea, aiming for a wider audience and early feedback

The app has not been used yet by "normal users".