Product Development Is Like Driving in a Fog

We shouldn't build most of features we envision during product ideation. At the early stage there's no point in planning too much in detail as we have limited visibility.

The ideation part of creating a new product is fun. We envision all the ways in which the product can be useful. We go as far as to picture specific features that are indispensable.

If we are smart, we don’t jump to the building part right away. We go through the discovery phase. Its basic goal is to surface and challenge the most critical assumptions behind the product idea.

Let’s assume we can’t invalidate the idea from the outset, before we develop anything, or that we stumbled upon one of those relatively rare concepts that actually stand the scrutiny. The next step is figuring out the scope of the earliest version.

BTW, I deliberately use “the earliest version” rather than “MVP” (Minimum Viable Product), as the latter term has lost all meaning.

Either way, we end up with a scope definition structured in one way or another.

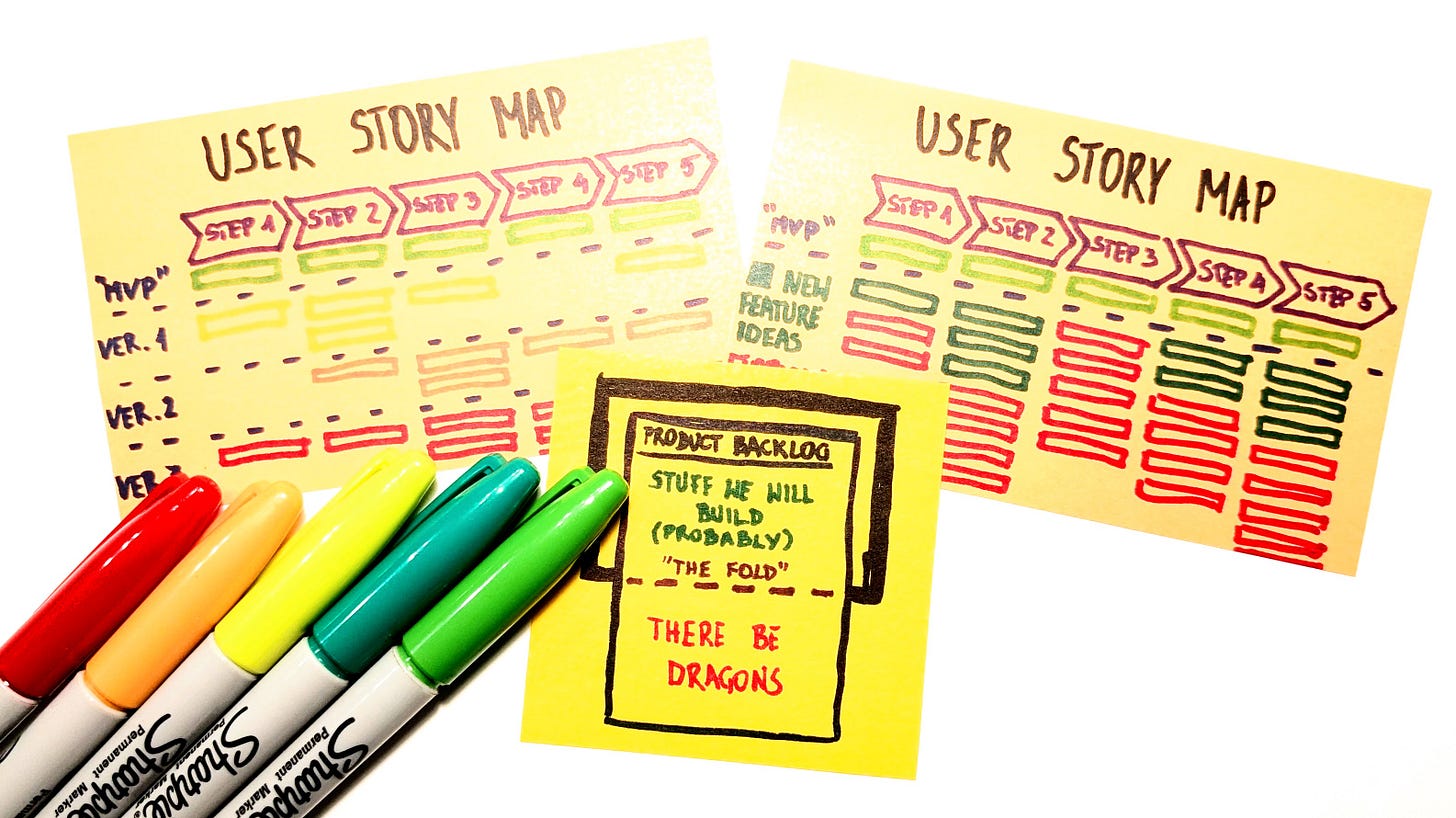

User Story Map

At Lunar Logic, when we are at this earliest stage of scoping, we tend to rely on user story mapping. Now, before you frown and say that Agile is so 2020, I was never a fan of a user story as an atomic work item for product development teams. The user story part is not that important, though. The way mapping happens is.

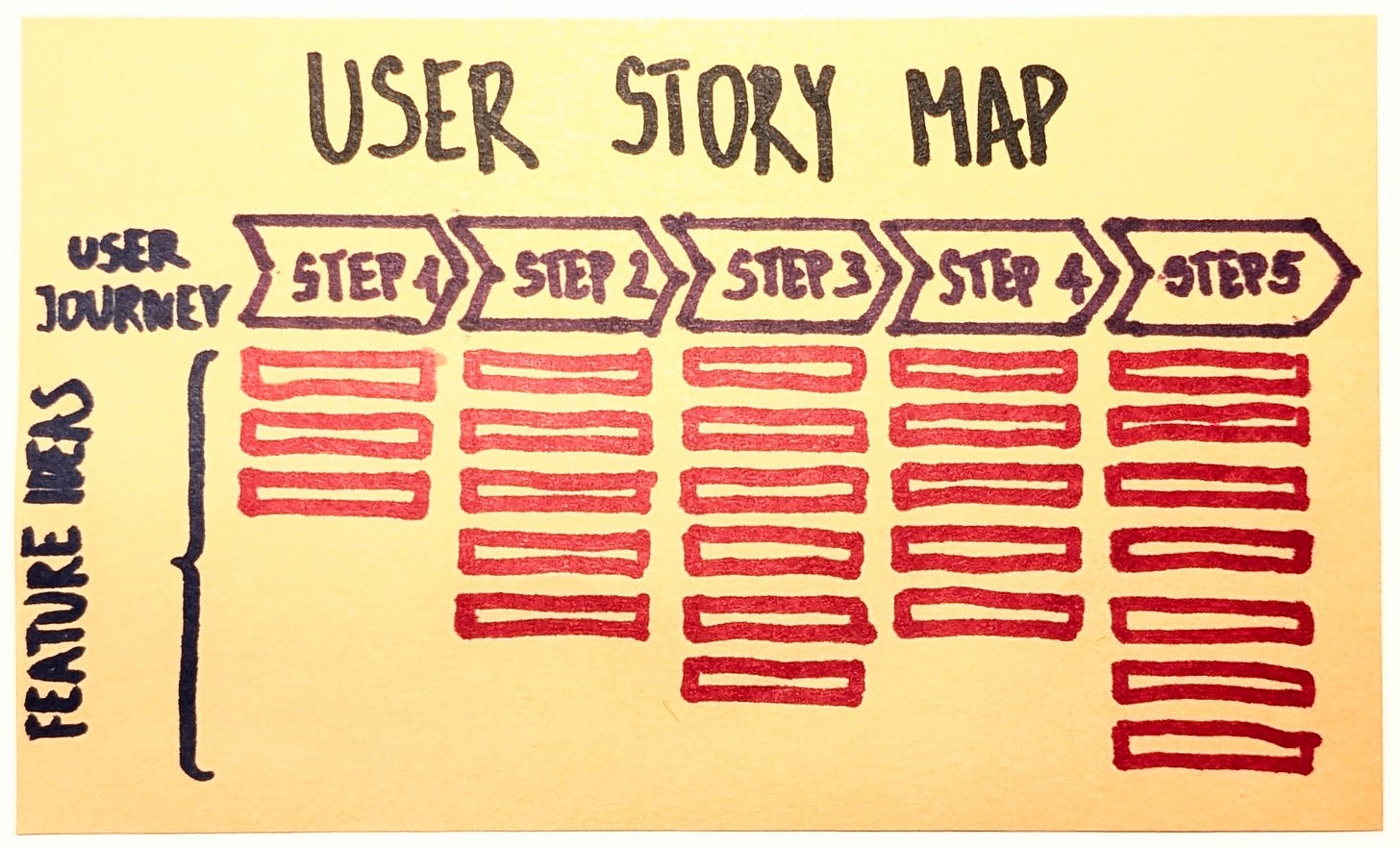

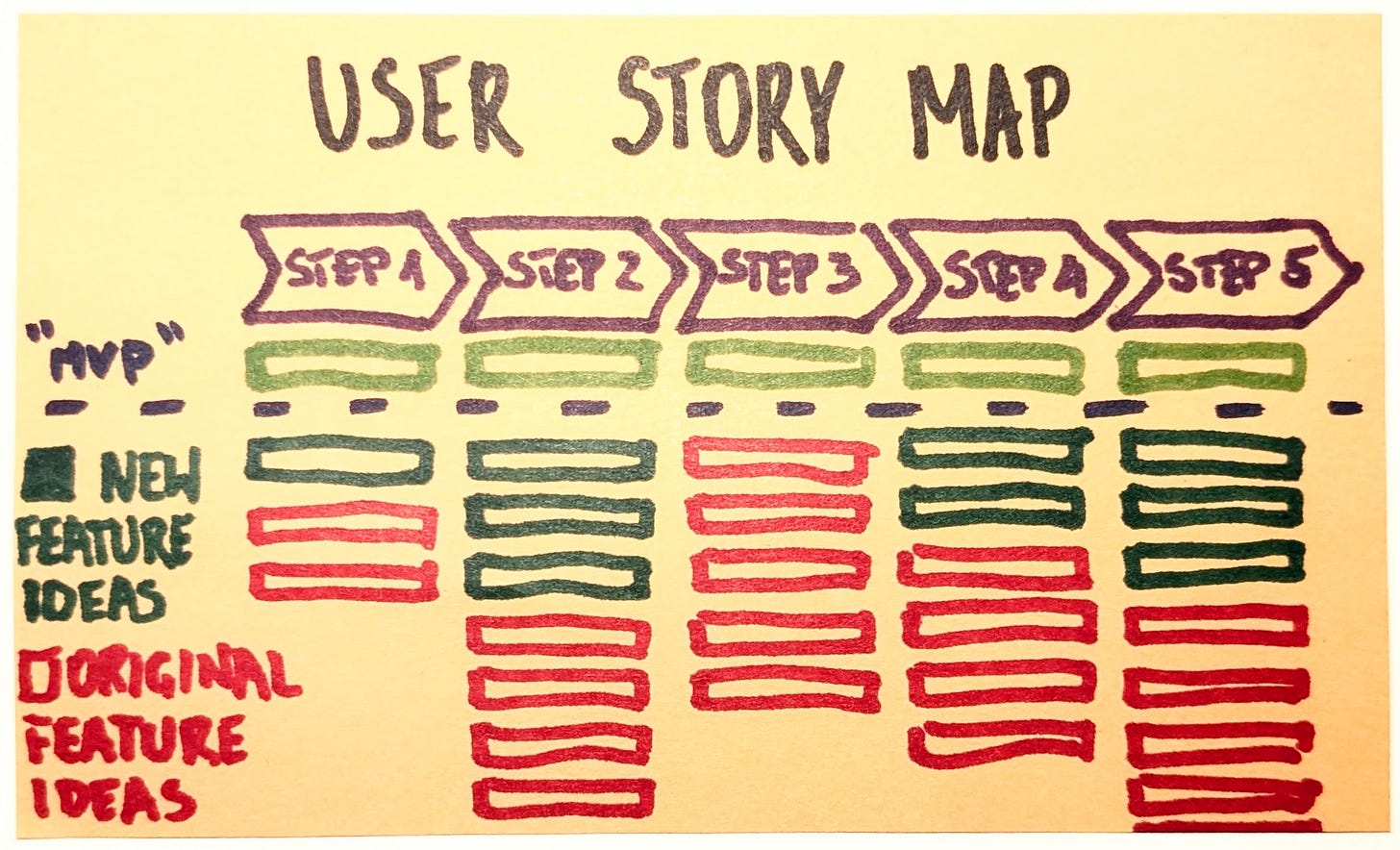

The basic idea is to create a path or journey where a customer uses the product to achieve a core outcome (think: from registration to a purchase on an e-commerce site). Under each section, we group all the features allowing a user to complete that step.

The features may be alternatives, like logging in with email, magic link, Google, etc. They may as well make the experience richer, like a product search, an advanced search with categories, a search with category-specific filters, etc.

User Story Map Drives MVP Scope

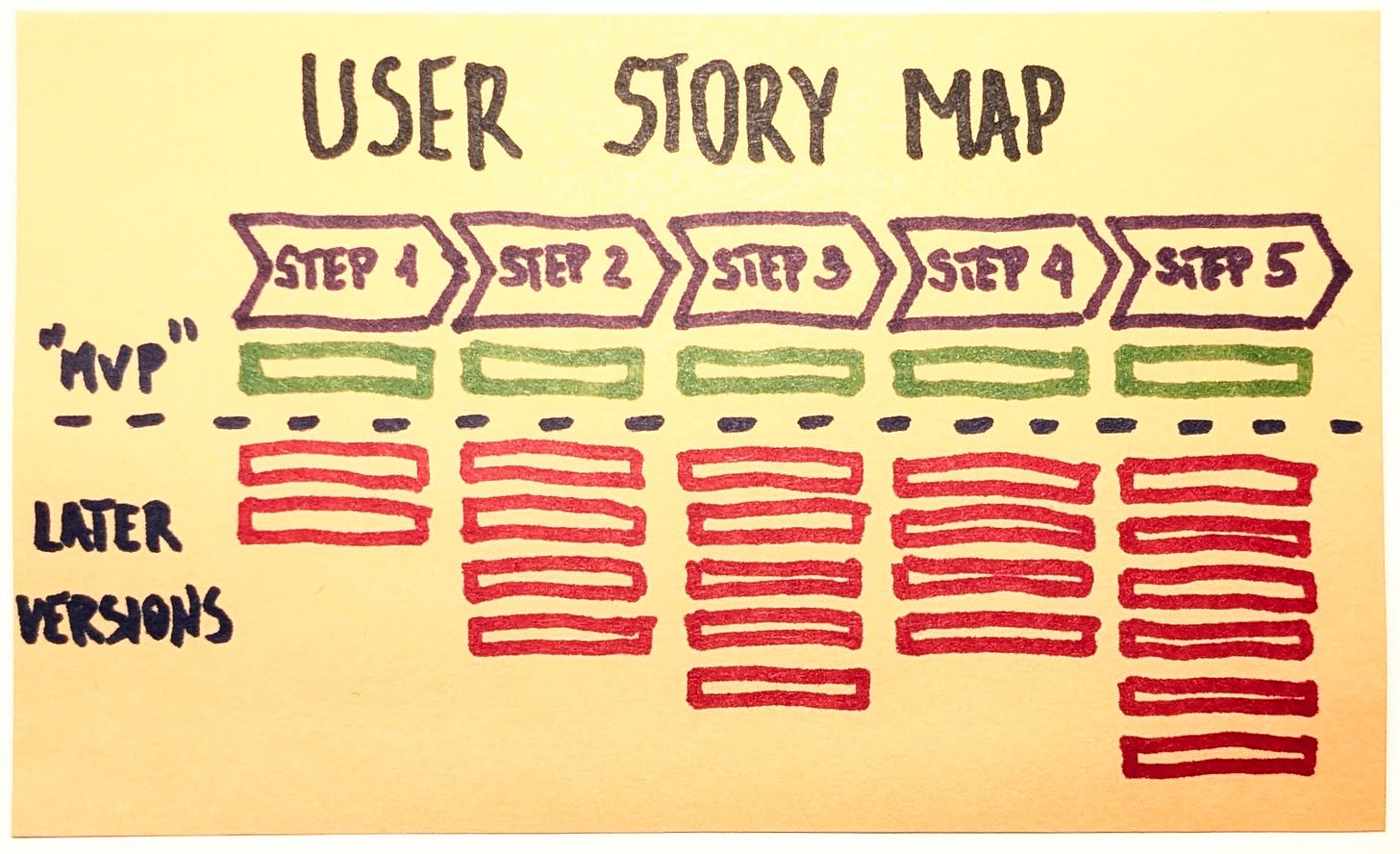

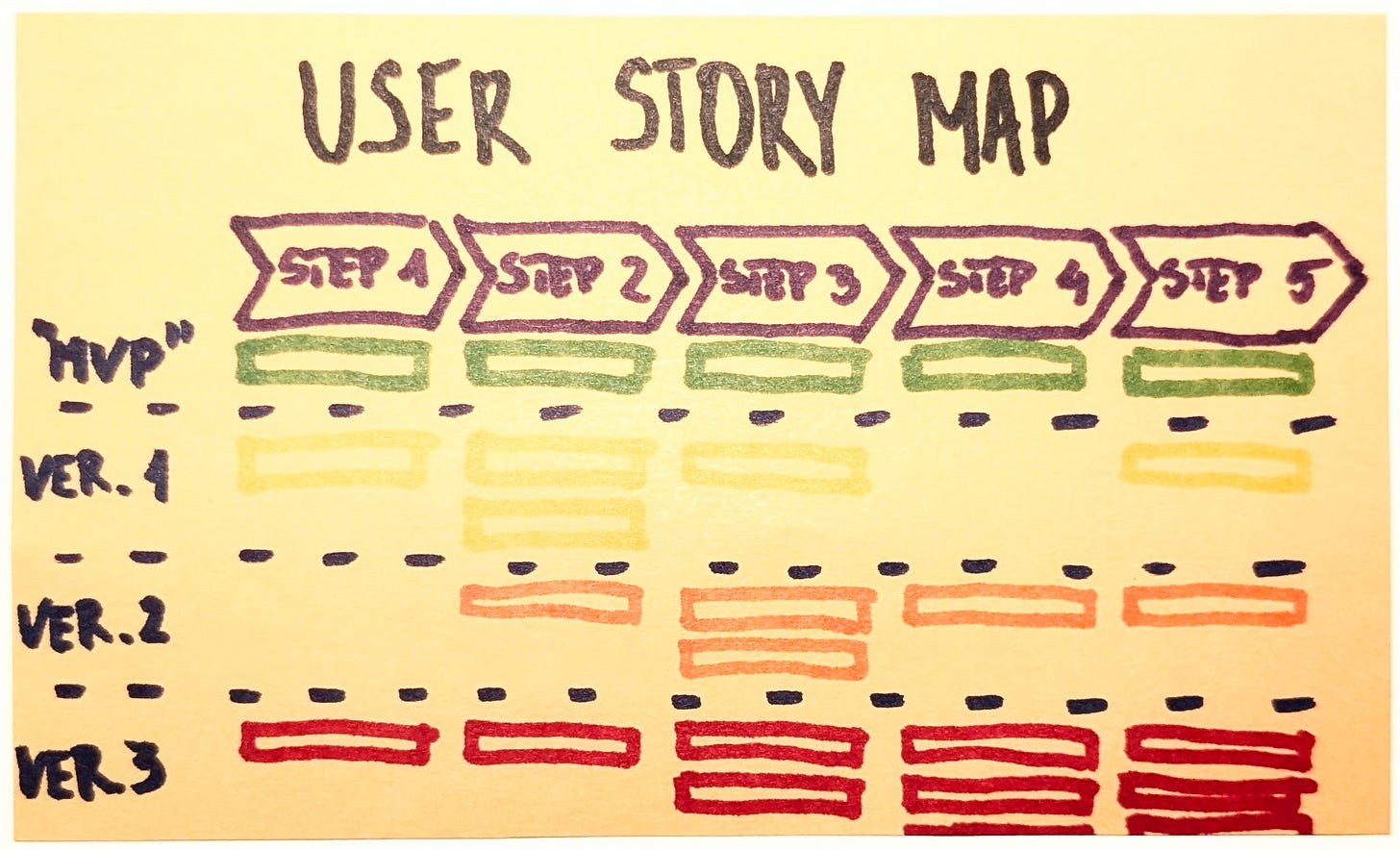

A big reason to map all features to an entire user’s path is to figure out which parts belong to the earliest version of the product. One tactic is to pick the simplest sensible part of every step of the journey. Together, they would constitute an MVP (or the earliest version).

Now, if you read this and wonder why the technique is called a user story map and not something like a customer journey map, then, well, I don’t know either. Maybe aside from the fact that the latter name was already taken. By the way, a customer journey map is a handy tool during discovery as well.

Also, the original idea was about “working with user stories in agile development a lot easier,” but it works great whether you care about user stories and agile or not.

Either way, once you have figured out the map, it will look roughly like that.

Anything above “the water line” is what goes into the earliest version/MVP. And yes, having just one feature out of each pile is what we aim for.

Everything below the fold is things for later. We’ll use them in the next product increments as we make the product better, more appealing, and everything.

The Biggest Secret of Product Development

Remember how I said that we’ll keep those feature ideas for later versions?

That’s a lie. We won’t. At least most of them, anyway.

We imagine that we’ll cut through those feature ideas, batch after batch, till the product is finally what we have envisioned. It happens, well, just about never.

“No plan survives first contact with the enemy.”

Helmuth von Moltke

As one of the greatest military tacticians of all time suggests, whatever we initially planned (the scope) will be shattered by the time we see the live action (the product release).

The moment we release a new product, we get either kind of feedback:

People don’t use it. Sure, we can double down and keep building, but that’s only going to burn our resources and change nothing.

People do use it. However, the feedback we receive from those early adopters is different from what we envisioned “before the first contact with the enemy.” Thus, we now have all sorts of new ideas on what to build next.

In the first case, we can scratch the user story map altogether. In the second, it suddenly looks very different.

If the order of features reflects the priority (the higher something is, the more important it is), the new insight will fly high. After all, it comes from actual product usage, not from hypothesising. It’s validated. At least it’s validated more than ideas whose main merit is that we’re in love with them.

Here’s the biggest secret of product development. The new ideas will always be arriving. They will always be more validated than our theoretical speculations, so they will be prioritized. Thus, we’ll never get to build the original scope.

Product Development Is Like Driving in a Fog

Imagine you’re driving a car in a thick fog. You don’t see miles away, but only the nearest surroundings. In such a case, you focus on observation and respond to the stuff that emerges from the fog. If you know the terrain, you may have some idea of what might happen, but since you can’t see all the moving parts ahead (pedestrians, other vehicles, traffic lights, etc.), you can’t plan too far into the future.

Product development is like driving in a fog. We can see only thus far, and we necessarily respond to new insights as they emerge. What’s more, we prioritize these new developments as they are more relevant to our situation than we initially thought.

There’s literally no point in planning months ahead in detail, since we know things will change. That detailed user story map we discussed above? Its main purpose is to provide enough context to figure out what the first version should be.

Whatever’s left below the waterline may be (will be) irrelevant soon enough. If we want to keep the map up to date, it has to be alive. That, in turn, means adding stuff to it. A lot of stuff. More than we can chew through.

Those old feature ideas will be pushed lower and lower until they become the main prize in a last-man-standing doomscrolling contest.

Product Development Planning Horizon

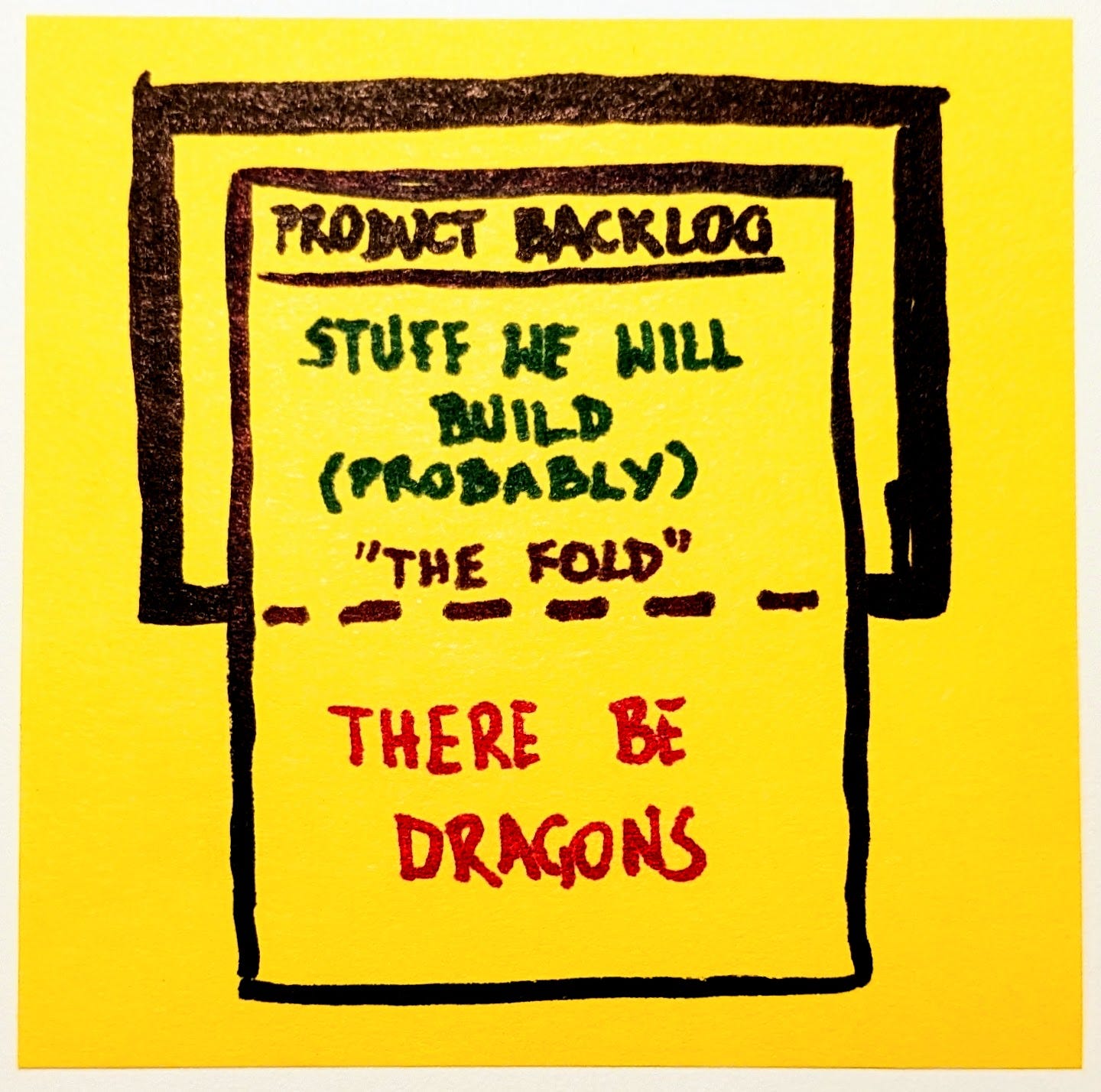

I have an informal rule of thumb. Whatever is in a product backlog should fit on one screen and remain readable. It’s like good ol’ “above the fold” in web design. If you can’t see it without scrolling, it may as well not exist at all.

The same is true for a whiteboard, too, by the way. We can fit maybe a dozen sticky notes in a single file column, and that’s it.

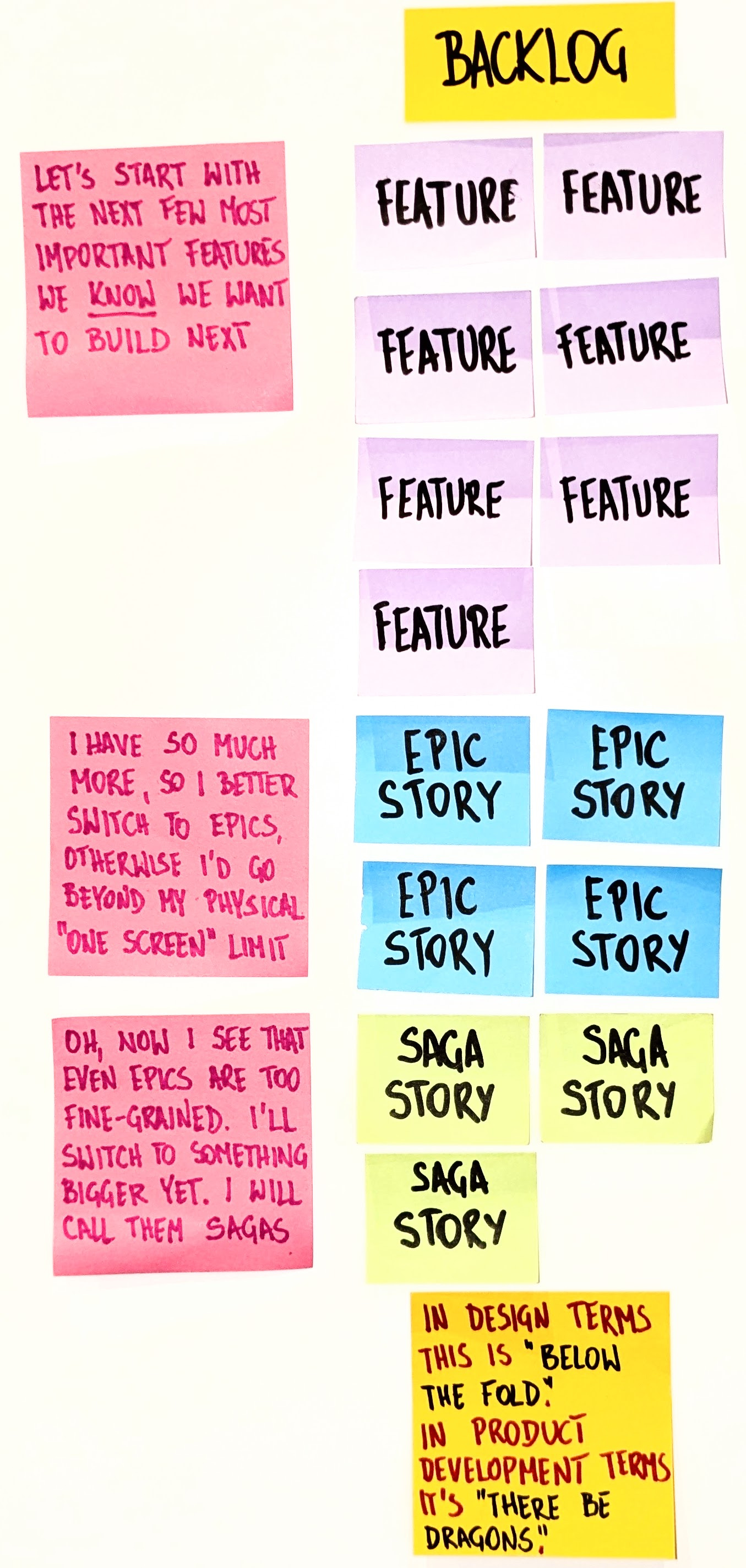

But hey, we need a strategic direction that goes beyond just the next 10 features. How could we possibly have a coherent product vision without an option to focus on bigger chunks of work?

That’s where we combine different product development horizons. My limit was “whatever fits a column without scrolling.” I never said anything about all the items being fine-grained features.

So once we populate the backlog, we should incrementally switch to coarse-grained items, like epic stories (or saga stories if epics are still too small).

Not only do we stick to the “above the fold” rule of thumb, but we also explicitly acknowledge that we drive in a fog, and we can’t know the details of what’s far ahead. Even better, we maintain alignment by highlighting those few important big things awaiting us in the near future.

Just-In-Time Planning

We only need more details as we plan to move to building things. There’s no point in designing the specific implementation of an epic story (which is major product functionality) unless we know we’re going to commit to building it. And if it’s the third epic in the priority order, there will be a lot of stuff that will happen before we’re ready for that commitment. That is, if we ever get to that point.

Any detailed planning we do way ahead of time is almost guaranteed to be a waste. Remember, we drive in a fog.

As in a first-person-perspective video game, the surroundings are rendered in more detail only as we get closer to them. There’s no point in spending GPU resources on preparing all the fine details of that fine city on the horizon if a player is going to turn their back and go in the opposite direction.

And it’s not like we get only “no details” and “all the details” as binary options. We get just enough detail for the human eye to process on a modern monitor.

By the same token, that’s how we should work with product development. The closer the actual development work is, the more details we should have, and the more planning we should do. Worrying about what we’re going to do in September next year isn’t the best use of our mental capabilities.

We Don’t Build Features We Envision at the Early Stage

To make things worse, we know that more ideas will arrive since we learn from our customers. All. The. Time. Planning in detail ahead of time is basically a guarantee that we will end up with a lot of really old work items. That is a bad idea.

“Work is like yogurt. Eventually, it goes bad and when it does, it’s very very ugly. If you have a task that’s been sitting there since the Obama administration, it’s not a task anymore. It’s a historical artifact. Throw it out.”

Jim Benson

So we either plan ahead and then throw out the rotten tasks, or we zoom into work only as soon as we really need it. The latter is a more efficient tactic.

Either one means that you will never build most of the stuff you envision when you ideate your product.

I experiment with a tool that confirms the post’s been written by seemingly quite an OK human, and not an AI: 웃https://okhuman.com/NytsYw